|

About OgreCave and its staff

|

|

by Lee Valentine

In 2010, in cooperation with Czech Games Edition, Z-Man Games released Dungeon Lords in the United States. This new board game comes from designer Vlaada Chvátil, who also designed Galaxy Trucker and Space Alert (featured in OgreCave's 2009 Christmas Gift Guide), among some of more popular offerings. Obviously themed as a board game successor to the 1997 Electronic Arts PC game title Dungeon Keeper, in Dungeon Lords players play evil overlords (or is that underlords?) overseeing the building and stocking of terrible fantasy dungeons. Like Chvátil's earlier design in Galaxy Trucker, the premise is to invest time into building something up only to watch it get knocked down. After every four calendar seasons of construction, several adventurers will enter your dungeon to test their mettle against your malevolent creation, to try to convert it to light and goodness, bringing sunshine, grass, and flowers to replace dark granite walls and deadly traps. The game lasts for two such game years, forcing you to survive invasion by fantasy adventurers twice. The goal is to score enough points on your Ministry of Dungeons licensing exam to be declared the Underlord, or at least to receive the minimum number of points to get a license to operate a dungeon without outside supervision. At its heart, Dungeon Lords (DL) is a deeply themed worker placement and resource management game. These two elements work in tension with each other. You must compete with your fellow players to get in line to acquire specific resources. Most resources you acquire will in turn have a price attached that must be paid using some other resource as a currency. This can become an intricate juggling act – for example, it's necessary to have gold to buy food to feed your imps that mine for gold in your dungeon. You need money to make money, and hopefully you make more than you spend. Manage your workers and your resources well, and you will be overseeing the running of a well-oiled machine. Let the wrong resources get too severely depleted at the wrong time and your ability to accomplish much of anything can grind to a halt.

Gameplay: 4-player basic game

Buying positions are acquired using a RoboRally-like set of programming cards. Each player has a set of cards that correspond to the possible season actions in the game. There are three positions for new order cards on each player's "player board" (a.k.a., "dungeon board"). Players select their orders, placing them face down. Then, in turn order, each player flips over their first instruction, and sends their first minion to a buying position under a given action. Then, the second order is flipped and minions are assigned actions as before. Finally the third order is handled. Your order positions on your dungeon board effectively weigh how much you value a specific order. So, even if you are in fourth place in the turn order, if you are the only one to place the "hire monsters" action as your first order, then you will get the first buying position for that action. If everyone else did the same thing, however, and you are fourth in the turn order, then your minion is sent home with nothing to show for your efforts, as there are only three buying positions. There is tension in this dance for position, as being earlier helps guarantee that you get something, but sometimes holding the second or third buying position allows you to milk a little more out of that action for the resource cost than the first player could. One intriguing resource puzzle for sending out minions is that your second and third order each season will be unusable in the following season. These cards are left face up to help other players know what you can't do, and to haze you if you desperately needed to use those actions again. The card in your first order position is usually returned to you after worker placement to use season after season, along with any orders you had locked as unusable during your previous season. I have played Agricola only once, but I didn't like the nature of the worker placement in that game, where one player could sometimes chose a resource and thereby deny it to all others. The fact that there are more buying positions in DL, combined with a knowledge of what some people cannot choose as an action makes DL a superior worker placement game to Agricola in my eyes. In addition to jockeying for buying positions, players also interact using a clever little mechanism called the Evilometer. If you hire a troll he eats your food, but if you hire a vampire then he turns the local villagers into food and sends the signal that you are the sort of Dungeon Lord who is exceptionally evil. As its name implies, the Evilometer is a measure of how evil or how (relatively) friendly you are. During each of the last three seasons each year, adventurers queue up to be assigned to adventuring parties visiting specific dungeons. Thieves disarm traps, mages cast annoying spells, priests heal, and warriors have more hit points. The adventurers in each season's queue are nominally ordered from the most powerful adventurer to the weakest. When it's time to assign adventurers to a dungeon, the most powerful one is assigned to the dungeon of the most evil Dungeon Lord, while the easiest is assigned to the nicest Dungeon Lord. Since the game gives you a sneak preview of the adventurers that are looking for work that season, you have time to adjust your rank on the Evilometer to help you get just the adventurer that you prefer. The only problem is, all the other players are doing exactly the same thing. While adventurers at the front of the queue are more powerful, sometimes power is relative. If your dungeon uses traps as its primary defense then you might want to steer clear of the thief in the queue. However, even if the warrior at the front of the queue is hard to kill, it might be better to have him visit your dungeon than a lowly priest if all your monsters are evil vampires who can't attack priests. Even more threats from the surface world can array against a Dungeon Lord. There is a warning line on the Evilometer, and if you reach it before the other players, you are assigned the Paladin for that game year. The Paladin has the toughness of a warrior and all the powers of a thief, wizard, and priest combined. The Paladin for the fight at the end of the first year is tough. The Paladin for the second game year is absolutely gross and will very likely rain on your parade if you get too evil. There are only two ways to get rid of the Paladin: kill him, or wait until someone else becomes more evil than you and attracts the Paladin away. By the end of the fourth season of each year you will have amassed a dungeon full of monsters, traps, rooms, and tunnels. You will also have three adventurers (or four if you attracted the Paladin) waiting to conquer your dungeon. At this point you prepare for combat. There are four rounds of combat and one Combat Card for each round. The Combat Card lists a spell that wizard adventurers in your dungeon (if any) will try to cast, and it also tells how much damage the adventurers will take from the rats, uneven floors, and intra-party bickering that is the by product of all dungeons. This damage is called Fatigue. You choose a spot in your dungeon for the first fight to occur, where your traps and monsters in that location, as well as the adventurers trying to defeat them, all let loose with their various payloads like a giant fantasy-themed Rube Goldberg machine. If all the adventurers are knocked out and tossed into your prison, you rejoice. If not, the remaining adventurers dismantle the traps you used, knock out the monster you sent, conquer that location, and march further into your dungeon to conquer again. This is like a game-within-a-game, where your resource management decisions from earlier in the game year give you the toys to wage war using a complex order-of-operations puzzle mechanic: traps fire off (if they weren't disarmed by thieves), then fast spells, then monsters, then slow spells, then healing, then Fatigue, then the adventurers conquer your dungeon tiles. That's the basic overview of the game. You repeat this process for two game years (eight total seasons) and two combat sequences and then a winner is declared. The game uses a point scoring mechanism that takes into account most features of the dungeons, assigning point-scoring titles one-by-one, such as naming the player with the most tunnels the Tunnel Lord and giving him a few victory points for his diligent tunneling. The player with the highest total score is declared the Underlord and the winner of the game. Unfortunately, there are lots of things to subtract from your point total as well, like unpaid taxes to the Ministry of Dungeons, who levies an annual property tax on each Dungeon Lord based on the size of his Dungeon. Similarly, you lose points for each conquered tunnel or room tile in your dungeon.

Different Modes of Play DL has a basic and more advanced version. The rules in the advanced version are only slightly more complicated, but they add a substantial additional drag on already tight resources. The basic version throws plenty of hate against the players, but the advanced version adds even more taxes and nickel-and-dime costs for hiring monsters. Once you know the advanced version of the game, there are two web-extra ways to play published online by Czech Games Edition. The components for these extra modes of play come with the game, but oddly enough, the rules are only found online. Other than arguably the two-player game's order selection, a lot of the player-versus-player interaction in Dungeon Lords is indirect, like jockeying for a specific spot on the Evilometer. The extra modes of play involve passing out magic items to enemy adventurers, and one mode specifically allows you to choose which player's assigned adventurers get which magic items. This can add a little extra PVP if you were missing it from the basic or advanced games.

Crushing Defeats

Components and Packaging All the boards have a mixture of fantasy artwork and game-related iconography. There is a lot of iconography to memorize in the game, but if you are a serious gamer you will internalize it in short order if you have at least one player at the table who has read the rulebook. I found the iconography much more evocative and easier to internalize than in Race for the Galaxy, for example.

There are nice, clean-looking game cards for combat cards, traps, minion orders, and scoring. They are a bit thin, and I worry in particular that the orders cards will become marked over time. These cards are closer in size to a business card than a poker card and so will be somewhat harder to find decent card sleeves for if you decide to protect your cards. Thick counters represent all monsters, rooms, tunnels, and adventurers. If you receive a set that is properly die cut, then you'll enjoy the quality of these particular components. Unfortunately, Z-Man Games reports that about 1% of their product run contains counters that are not cut well, resulting in tearing and marking of counters on the corners and edges even with careful punching. I received such a flawed set for review. After the tearing happened to a number of pieces even though I was being pretty cautious about punching out the counters, I switched over to using a craft knife to carve out the tokens individually. This gave a slightly rough edge, but stopped the obvious marking I was getting on the earlier counters. The results of my efforts were tokens that were brand new, but which looked worn and somewhat roughly handled. The game boards are of mid-grade quality, and all are either non-folding or bi-fold boards. None have particularly heavy reinforcement at the joint. None have protective wrapping at the edges. Some lay fairly flat while others have a slight rise or bow to them because the joint at the fold does not fold out perfectly. As long as you can figure out which edges to open the boards on, they should last, though perhaps not as well as a higher quality board.

Rulebook While the rules are numerous and the gameplay is intricate, the game comes with a variety of play aids to help track the order of actions taken in the game. The backs of dungeon boards combined with the rulebook help to form a four-part tutorial for the combat section of the game, giving players a leg up to help them understand what it is they are stocking their dungeon with. This was an extremely clever use of board real estate, and I was pleased with its inclusion. In addition to functioning as a tutorial, if the person you are demonstrating the game to can't follow the tutorial, it's a good way to find out early on that the game is probably not for them.

Conclusions While the game is expensive, it comes with numerous components so you aren't getting an empty box of air. I really liked the two-player experience, but there was some additional time and fiddling with components that you just wouldn't have with four players. As a result, I think this is primarily for gamers who have ready access to gaming groups consisting of four self-professed gamer geeks. I say "gamer geeks" because I worry that this game is too complex for your friends and family members who aren't hobby gamers. Particularly if you have to manage a dummy board your first few games, this game can run a bit long. You should allocate three hours or more the first time you bring this to the game table to take into account combat "analysis paralysis" during your first outing as well time to learn the rules. If you have a regular group of three, or ideally four gamers, if you enjoy subtle manipulations as opposed to direct conflict with your fellow players, and if you are looking for a game dripping with fantasy theme, then this is probably a good fit for you. If your group consists of players who enjoy lighter games, shorter games, or more direct player-versus-player interaction, then I cannot recommend this game. Personally, I really enjoy Dungeon Lords. I do not mind a heavy brain drain on occasion, and I laughed and groaned hard when I got the second-year Paladin and the adventurers went on a slash and burn expedition through my dungeon. If this sounds fun to you, then consider picking this one up.

Retailers The DL box is very attractive, and its theme and backstory are likely to make some sales. As I noted earlier, I am not sure whether people browsing the game will associate such light-hearted artwork with such a detailed game, so as a retailer you may have to help make a marriage between this game and the right customer. DL is easy to hand-sell with a quick sales pitch to the right customer – the theme of being an evil overlord in charge of a dungeon getting invaded by fantasy adventurers will be a winner with customers who play both fantasy RPGs and board games. Unfortunately, the game doesn't make for a quick five-minute demo like some other Euro-style games. As a result, I suggest offering a discount to your local alpha gamer if he is willing to come out and run a couple of full-game demos of this product. That's where you will pick up some extra sales.

Lee's Ratings:

Overall: B+ * I had really poorly die cut counters (about a C+/C for those), but other components were decent. Since the counters are attractive and thick, if you receive better counters than I had (which Z-Man Games claims will happen the majority of the time), then you might rate the overall components in the package at a "B" overall.

Links:

|

||||||

Dungeon Lords

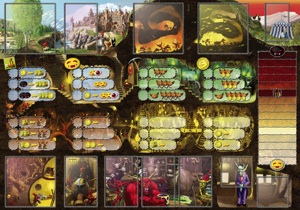

Dungeon Lords The main board of the game is called the "central board". It is on this

board that most of the player interaction takes place. Each player has

three minions to send to the central board each season to program in his

workers' actions for that season. The available actions are: get food,

improve the Dungeon Lord's reputation (make him appear less evil than he

is), dig tunnels, mine for gold, recruit imps, buy traps, hire monsters,

and build a room. Most of these actions have three buying positions

located under them. Each buying position has a different cost and a

different return on investment than the one before it. For example, the

first minion sent to get food during a season gets two food for one

gold, but drains the village's precious resources. The third minion,

however, slaughters villager's and pries food from their cold, dead

hands and steals back the gold paid by the first minion, all the while

sending signals out to the adventurers waiting in the wings that his

master is truly malevolent. Note that since most actions have only

three buying positions and because DL is a four-player game, one

of the players will have to forego using a particular action each round,

either because he has planned to do so, or because he is hedged out by

his fellow Dungeon Lords.

The main board of the game is called the "central board". It is on this

board that most of the player interaction takes place. Each player has

three minions to send to the central board each season to program in his

workers' actions for that season. The available actions are: get food,

improve the Dungeon Lord's reputation (make him appear less evil than he

is), dig tunnels, mine for gold, recruit imps, buy traps, hire monsters,

and build a room. Most of these actions have three buying positions

located under them. Each buying position has a different cost and a

different return on investment than the one before it. For example, the

first minion sent to get food during a season gets two food for one

gold, but drains the village's precious resources. The third minion,

however, slaughters villager's and pries food from their cold, dead

hands and steals back the gold paid by the first minion, all the while

sending signals out to the adventurers waiting in the wings that his

master is truly malevolent. Note that since most actions have only

three buying positions and because DL is a four-player game, one

of the players will have to forego using a particular action each round,

either because he has planned to do so, or because he is hedged out by

his fellow Dungeon Lords.

The game contains nice plastic and wood bits to keep track of various

resources and features in the game. Most of these are pretty abstract

like slime green squares for food. These are largely appropriately

sized for handling, but parts of the board's pretty art get buried under

mountains of components after you setup the game for play. My favorite

plastic components are tiny, custom sculpted imp figures, which help to

add to the play experience.

The game contains nice plastic and wood bits to keep track of various

resources and features in the game. Most of these are pretty abstract

like slime green squares for food. These are largely appropriately

sized for handling, but parts of the board's pretty art get buried under

mountains of components after you setup the game for play. My favorite

plastic components are tiny, custom sculpted imp figures, which help to

add to the play experience.