|

About OgreCave and its staff

|

|

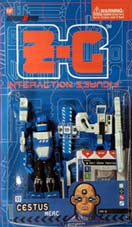

by Mike Sugarbaker Yes folks, this is the game with the robot action figures. They come in three colors, red, green and blue. The three are not only different models with different starting sets of equipment, but come with different character cards with different abilities, and represent three different factions in the game's story. (Factions are pretty spongy in Z-G, unlike a lot of CCGs you're used to. Nothing in the game mechanic or cards really deals with factions in a hard and fast way. You won't find them limiting your selection of cards or equipment.) The figures look simplistic compared to the collector's-market robots you've probably seen, the ones based on video games or anime. Z-G's figures are vaguely anime-ish, and are much better-articulated than low-end figures for kids, but they look like figures for kids. The way Z-G is packaged, in a cardboard-backed blister pack with a playmat, is the other indicator that Atomoton thought they'd hit the Pokemon market with this game. Well, if they'd wanted to sell to 12-year-olds, they should have designed a game for them, but we'll get into that. The figures as they exist now are functional, not exactly ugly, in fact sort of charming in their way, but in future sets they ought to be sculpted a little more toothsomely to appeal to gamers who'll actually be able to cope with the rules. Anyway.

All zGear cards have a Move statistic, as well as a Range stat for their actual attack. Movement is measured in lengths of the game's cards - that's the first niftily elegant thing that struck me. (It may also be the last. Elegance is not really this game's watchword. Although things do fit together and seem to be balanced well, Z-G tends toward the more-is-better side when it comes to game mechanics, and it can feel messy and overwhelming.) The positioning of figures on your game table does count tactically, especially for Zone attacks, whose area effect might be four cards long by three cards wide if you get far enough away. If you play with terrain, as Atomoton strongly encourages you do, then, well… can you say "death from above"? I knew that you could. The match-to-strike mechanic is the cleverest of Z-G's innovations, but also the one that makes the game designer in me the most suspicious. At first glance, it's really, really random. At second glance, it starts to look like the best strategy is to memorize what's on the ends of all the zGear in the game (and then build a degenerate Mode deck that lets you target attacks to your little, sour heart's content). That's not really much fun, but fortunately, it wouldn't help you much either. The real key to the game is in the ability to "retest," a sort of controlled do-over granted you by special abilities on Mode cards. Between that and attacks that let you Scan (preview the card you're attacking) and Targetlock (force a card drawn as an attack's target to hang around, face up, for your next attack), you can start to have a little control over the randomness. (Or at least feel like you do. Detailed statistical analysis of many, many games might show otherwise, but who has time for crap like that.) I can easily list off some of the things I don't like about Z-G. Its single biggest problem out of the box is that the only rules provided are on the half-size "playmat," rather than a rulebook, where you can afford to be chattier. Even considering the poor job most playmats do of communicating a game, there are just so damned many rules in Z-G that putting them on a playmat does them a great disservice. Remembering what all your options are at any given time would have been a challenge regardless, but the playmat format just encourages you to gloss over things. If they were trying to "write down" for kids, they failed utterly - every sentence is important and subject to misinterpretation, and no time is wasted on elaborating or explaining anything. This is definitely the kind of game that people should be taught, rather than trying to learn it themselves. As decadent, foolish, and five-years-ago as the announcement of a since-canceled Z-G "Battlebook" strategy guide looked to me at first, it might have been a good idea if they had gone ahead with its publication. (As of now, you can reportedly get at least some of it at Atomoton's web site, and a straight Rules of Play reference document is available on related web pages. You still have to dig around for it, though.) Does everything that's in there need to be in there? It's hard to say. My league has seen precious little use of the Stances, which occupy a sizable box on the back of the playmat. Stances are formal positions you can put your figure into (if you can get it to stand up, that is) which confer special abilities, and require spending Move points to get into and out of. I think I've seen them used once in a dozen games… but these are games with people who've been buying cards like nuts. In a game with just two starter kits (meaning the default zGear and no spicy, delicious Mode cards), you need a little extra tactical dimension, in case people get too familiar with the zGear and the whole thing gets to be rock-paper-scissors. So, we have Stances, which help keep the game solid in an out-of-the-box situation and don't get in the way otherwise. Well, okay - I wouldn't call that "elegant" in a purist, game-designer sense, but as a practical solution to a practical problem, I have to say I admire it. So, for a better example of how woolly the rules can get, let's delve a bit further into the CCG-centric aspects of the game. Once you start buying cards and playing the advanced game, it becomes clear that Z-G is for gamers, not for Harry Putterers and shorties in Pikachu jammies. You don't have one deck in Z-G: you have a zGear deck, and you have a Mode deck which contains everything that isn't stuck to your figure - special actions, support cards, and all that. The Mode deck is the deck that is drawn from and depleted in the usual sense, but Mode cards never go into your hand. Instead, they always go right into your face-up Control Panel on the table. If you don't have any open slots, you've got to throw something out when a new card-drawing opportunity happens (and the rules for when you draw Mode cards are sort of subtle themselves). However, I have yet to have to need to discard something (granted, I'm playing with a fairly slim Mode deck so far), and the rules for how Mode cards can share a slot were still a bit unclear to me after several games. Your zGear deck, on the other, um, hand, you actually have a hand from. However, you choose this hand afresh each turn, and when you use a piece of gear, it goes back into your deck, which you then shuffle each and every time.

I'm inclined to say that Z-G is just not a game for purists, and leave it at that. It isn't purely anything. I mean, I guess it's possible to play this game without role-playing it at all, and still have a decent time. You might even be able to have fun without scenery, although you really should put together some rudimentary terrain. However, if you read enough of the cards to start getting a feel for the game world, give your contender a name and personality, and get into the weird anime-meets-WWF feel of it all, then and only then can you really get addicted. Some folks I've played with have treated it as a full-on minis game and given their figures custom paint jobs with hobbyist paints. And as far as the mechanics, you can't play this just as a minis game and ignore the card decisions, nor can you ignore positional tactics and rely on cards. You've got to think through both. Ah, yes: the Mode cards. When you buy a Z-G booster pack, you'll probably get a few enhanced zGear cards, meant to substitute for the defaults that come in the starter. The rest will be meant for your Mode deck. Mode cards can generally be sorted into three types: Arena cards, which give special rules to terrain and are laid out before play starts; Maneuvers, the "action cards" that are generally one-use and played on the fly during a combat; and everything else, but especially Syndic cards. Syndics are generic personalities your character relies on for support, and their traits determine which Maneuver cards with matching traits you may put in your deck. (All Mode and zGear cards also have a point value for deck-building purposes - a starting league character is 500 points, maximum.) Syndics also grant persistent special abilities that are available to you until the Syndic gets discarded somehow. They're how most retesting abilities become available, although you also see retests on Maneuver cards now and then. Syndics are as close as Z-G comes to having "land." They also tend to have the best artwork, with their "headshots" of interesting anime types. (The artwork standards are generally high, only falling apart on a few of the endless supply of Maneuver cards. Many cards are more design than art - indeed, the graphic design is a real star of the show here, and sometimes nearly interferes with usability, but doesn't quite. The zGear cards in particular can get very busy.)

The complexity of Z-G isn't in the card mix itself (not yet, anyway), so much as in the actual game rules. I guess that just means that if you buy starters and play the basic game, you can still get plenty confused. The game rewards study, however, making you feel a bit like those anime kung-fu heroes who are constantly remembering and/or discovering new tricks to add to their style. The cards don't often throw you way out into left field, instead offering a modest little exception here and a handy means to trigger an ability there. I'm not Mr. Suitcase, but I haven't seen any one card that looks overpowered all on its own. There might be some Syndic-and-Maneuver combos that are dodgy. (I'd worry more about some of the wild alternate attacks on souped-up zGear cards, but I also wouldn't trade those cards away for anything - state-of-the-art renditions of some of the equipment are where you see some surprisingly fun and strong stuff.) It's also very rewarding to play Z-G in a group or league, although two-player duels are still fast and fun. Having a community of players and card-traders is always good for a CCG, but a system as dense with weirdness as Z-G is best entered using the buddy system. Also, role-playing gets more fun the more people you get to perform for. See, here's the thing: in Z-G, unlike most miniatures games out there today, each player controls one actor with a lot of little tricks, rather than a squad of many actors. This makes Z-G a bit like a hack-and-slash role-playing game, even from a rules perspective. The folks at Atomoton have picked up on this and, as a throwaway line in a list of possible rules experiments, have more or less explained how to make such an RPG happen. In fact, hell, I'll explain it right now: a zMarshal with a big store of cards and a head for planning could easily construct a series of cooperative scenarios for a group of players, control some NPCs, and turn Z-G into every bit as much of a "real" RPG as the average dungeon crawl, or, say, every game of Rune ever played. To sum up: when you really sit down and think about it (as I now

have, at long last), Z-G is a remarkable achievement. It is a fairly

well balanced and rich game that manages not only to survive the

natural distractions that will tend to befall a bunch of gamers

with action figures in their hands, but to turn them to its advantage.

Z-G is a big enough world, speaking in terms of rules, that it's

difficult to say for certain that things aren't skewed, random,

broken or bent. But ultimately, a game has to be fun and has to

capture the imagination, and Z-G does so. So maybe it is

coasting on the fun factor, but if future card expansions and figure

add-ons are as careful and imaginative as this first set (and Atomoton

brings the aesthetic all the way in line with the game's real, older

target audience), I bet it'll be a nice, long ride. |

||

Z-G

is in fact a collectible card game, a miniatures game, or a role-playing

game. Hopefully you'll get some sense along the way of whether you

should throw some of your gaming money at it.

Z-G

is in fact a collectible card game, a miniatures game, or a role-playing

game. Hopefully you'll get some sense along the way of whether you

should throw some of your gaming money at it.

Also

included in each figure's box is a set of zGear cards, which correspond

to the set of plastic equipment and list their game stats and abilities.

Each round, you choose three of these zGear cards to attack, move,

and/or parry with (or use another of their special abilities). Attacks

always target a specific piece of equipment. Usually, this'll be

the top card of your opponent's deck of cards (in short, something

randomly selected from what they are not currently using - you'll

often find yourself considering how vulnerable you want a piece

of zGear to be when choosing your hand). Your Ulster, the protective

battle suit your character wears (that is, your unadorned action

figure itself), is one of these pieces of equipment. Lose it, and

you lose the game. More often, though, you get eliminated by attrition,

by being reduced to fewer than three pieces of zGear in all.

Also

included in each figure's box is a set of zGear cards, which correspond

to the set of plastic equipment and list their game stats and abilities.

Each round, you choose three of these zGear cards to attack, move,

and/or parry with (or use another of their special abilities). Attacks

always target a specific piece of equipment. Usually, this'll be

the top card of your opponent's deck of cards (in short, something

randomly selected from what they are not currently using - you'll

often find yourself considering how vulnerable you want a piece

of zGear to be when choosing your hand). Your Ulster, the protective

battle suit your character wears (that is, your unadorned action

figure itself), is one of these pieces of equipment. Lose it, and

you lose the game. More often, though, you get eliminated by attrition,

by being reduced to fewer than three pieces of zGear in all.

Moving

is all well and good, but eventually you have to attack. All cards

in Z-G have "dots" on each end. They're actually these

rounded pentagonal things that come in red, green, or blue. On zGear

cards, most of the dots have "blazes," little white symbols

that further modify the behavior of matched dots. When you attack

with a piece of zGear, you lay it face down, choosing which end

points at the enemy. The victim then draws the target card, spins

it in the air while dropping it on the table, then the cards are

turned over and the ends lined up. Whether you miss, hit, or hit-real-hard

depends on how many colors match on the dots, and whether the blazes

(with features like armor, armor-piercing, and weak points) block

or enhance those matches.

Moving

is all well and good, but eventually you have to attack. All cards

in Z-G have "dots" on each end. They're actually these

rounded pentagonal things that come in red, green, or blue. On zGear

cards, most of the dots have "blazes," little white symbols

that further modify the behavior of matched dots. When you attack

with a piece of zGear, you lay it face down, choosing which end

points at the enemy. The victim then draws the target card, spins

it in the air while dropping it on the table, then the cards are

turned over and the ends lined up. Whether you miss, hit, or hit-real-hard

depends on how many colors match on the dots, and whether the blazes

(with features like armor, armor-piercing, and weak points) block

or enhance those matches.

This

is a lot of counter-intuitive stuff to put into the basic concept

of a deck of cards. That's sort of exciting, but it's also annoying,

because it is never stated in crystal-clear terms that an idiot

(read: me) can understand. Instead, you have to let the express-lane

playmat prose slosh around in your head for a while until it all

suddenly becomes clear. (Or have a Z-Marshal or other guru to supervise

you, although how some folks have managed to bootstrap and figure

it all out is beyond me. Lots and lots of time online, I suppose.

The game's official ZG-Interaction Yahoo group is lively and diligent

about rules questions.) Is it just the purist in me that has trouble

warming up to a good game with bad rules-writing?

This

is a lot of counter-intuitive stuff to put into the basic concept

of a deck of cards. That's sort of exciting, but it's also annoying,

because it is never stated in crystal-clear terms that an idiot

(read: me) can understand. Instead, you have to let the express-lane

playmat prose slosh around in your head for a while until it all

suddenly becomes clear. (Or have a Z-Marshal or other guru to supervise

you, although how some folks have managed to bootstrap and figure

it all out is beyond me. Lots and lots of time online, I suppose.

The game's official ZG-Interaction Yahoo group is lively and diligent

about rules questions.) Is it just the purist in me that has trouble

warming up to a good game with bad rules-writing?

Also

falling under the "everything else" category in Mode decks

are: Drive cards, representing fundamental characteristics of your

character; Lode cards, which "plug in" to certain zGear

cards with a little yellow plus sign on them (took me forever to

find that in the rules); and Flaw cards, which give you additional

deck-building points in exchange for taking a disability your opponents

can use against you. These all grant special powers that persist

once drawn, like Syndic cards.

Also

falling under the "everything else" category in Mode decks

are: Drive cards, representing fundamental characteristics of your

character; Lode cards, which "plug in" to certain zGear

cards with a little yellow plus sign on them (took me forever to

find that in the rules); and Flaw cards, which give you additional

deck-building points in exchange for taking a disability your opponents

can use against you. These all grant special powers that persist

once drawn, like Syndic cards.