|

About OgreCave and its staff

|

|

by Lee Valentine

When one writes a review of the most popular role-playing game product to hit the shelves in years, one must take care not to appear to be either a spoiler (who wished he had written such a lucrative product) or a slavish fanboy. In writing this review of the Players Handbook I find myself unlikely to fall squarely into either of those categories. Judging by the materials presented in the Dungeons & Dragons 4th Edition Players Handbook (PHB) I have found a game which is a good game, but perhaps one that is not an ideal fit for people like me. The PHB represents a step forward in RPG evolution for people who love running combat-heavy classic dungeon crawl adventures. It is a step back in evolution for people who liked running political games or who liked characters with abilities more esoteric than zot, zap, and slash. It is oddly enough a game which, in terms of game balance of problematic abilities, represents a great leap forward in the ability of GMs to run epic quest-based games and mysteries. At the same time it somewhat discourages characters whose primary focus is on activities other than combat. In order to bring the reader to a point where he understands my perspectives, even if he does not agree with them, I'll discuss the mechanics presented in the PHB, noting specifically how the 4th Edition PHB differs from earlier versions of the game. While this type of focused comparison will be of less utility to readers who have never played D&D before, I expect that the vast majority of the readers who will find this review interesting will be those who have played some earlier edition of D&D and are merely wondering whether it's time to upgrade to the newest edition.

Overall Appearance The cover features a Dragonborn warrior and a human female Wizard (I'll get to them shortly). The characters have a special gloss laminated coating over them to make them really shine. The layout is easy to read, but particularly in the powers section, sometimes one page pretty much looks like any other, meaning it takes a little more visual effort to know where you are. To that end PHB includes lots of visual tabs on the outer edges of the pages that show the chapter and section. This helps you orient yourself as you page through the book. The book's binding is not perfect, and my PHB's cover seems to want to remain open a little bit with the front cover "hovering" over the first page. Perhaps the binding is merely too tight for its own good. It does not seem to have the 1E Unearthed Arcana problem of the pages falling out all over the place; just a problem staying entirely shut. The game includes a photocopyable, attractive, two-page character sheet (see the links at the end of this review for a PDF). In practice, I found that it lacked organized places to put useful information. For example, there's no space for the type of armor my character wears near his Armor Class defense statistics. The character sheet had insufficient space for languages and powers even for my first level wizard. None of the places to write-down weapons had columns for the range of my ranged powers and weapons. Inclusion of the character sheet was nice and it adds to the appearance of the product, but it was not as useful in practice as it could have been.

Core Mechanics In previous editions, magic was either automatic, or granted a "Saving Throw" to shrug off half or all of it's effects. "Saving Throw" is something entirely different in 4E. Players have four defensive ratings: Armor Class, Reflex, Fortitude, and Will. Each roll in the game pits an acting character against a static difficulty number (if the roll is unopposed by another character) or against the appropriate defensive rating of the defender. This decides whether a defending character is affected by an incoming attack, power, or effect. Therefore, Saving Throws do not actively resist the incoming attack as they did in previous editions of D&D. Instead, Saving Throws are typically a roll of 10+ on a d20 (a 55% chance of success), to shrug off an ongoing effect. You make Saving Throws for each ongoing effect that is still affecting your character at the end of each of his turns. While the game has a number of specific modifiers (attribute scores, half of a characters experience level, etc.), most of the general modifiers are easy to remember. A normal good modifier is a +2; a normal bad modifier is -2. Really good or bad modifiers are +5 or -5 respectively. So, it's often easy to adjudicate something without looking up a specific rule by using this simple rule of thumb. This uniformity of mechanics makes the underlying chassis of 4E much easier for a new GM to run adventures with. It will also make the game easier to teach to neophyte players.

Attributes and Character Building While players have some freedom to select their character's abilities, in general, each character is based around a character archetype, or "Class" - a familiar D&D concept. While there are resources to spend on options during character creation, there is no unified pool of common points available for the purchase of skills, attributes, and powers as in other games like the Hero System (Hero Games). Instead there are attribute points, skill slots, Feat slots, and various types of power slots. This makes the math of character creation fairly trivial. However, the division of the character up into a variety of non-transferable slots means that character creation is less flexible than in a pure point-based system, but is also much harder to abuse. While Attribute Scores for Strength, Constitution, Dexterity, Intelligence, Wisdom, and Charisma can be randomly generated, the game really encourages creation of an array of 6 attribute scores using a point buy system. Using this method, you start with a default array of attribute scores including one attribute that starts at a score of 8 and five attributes that start at a score10. You then are granted points to modify those values upwards. Adding more to an attribute score is a pure linear 1:1 increase until the attribute increase to 13, and then additional attributes cost more points per level. Your average attribute scores are higher when your maximum attribute score is lower. Attributes each convert into modifiers using the following formula: (Attribute - 10)/2, rounded down. Modifiers are used for multiple purposes throughout the game. The use of a 3-18 Attribute scale is largely a holdover from 1st edition (1E) D&D and really adds little except an extra layer of complexity, since you use the resulting modifier for most purposes. These Attribute modifiers are no longer tied to specific defensive scores in a one-to-one correlation - for example, you can either add your Wisdom or your Charisma modifier to your Will Defense. Attribute scores advance periodically throughout a character's life span as he becomes more skilled and gains a level of experience in his character Class. Each character Class has powers that focus on any of up to 3 different Attribute scores. This means that a player has to be careful not to crank up one of his character's Attribute to the exclusion of others if he wants to be able to diversify the type of powers his character will have access to. One-trick wonders are possible, of course (such as a Fighter whose only really high score is Strength), but there is now a place for a character who has a diversity of above average Attributes instead of just one gratuitously high Attribute score. There are 30 levels of each character Class in this version of D&D. Unlike previous versions of D&D which tended to have a "sweet spot" where they were neither too fragile nor too powerful (for example, 8th to 12th level characters), the 4th edition PHB seems to support play from 1st level to 30th level. Character level is a dominating force in 4E. Players add 1/2 of their level, rounded down, to all their defenses, to all their hit rolls, to all their attribute checks, and to all their skill checks.

Skills

Skills are much more broadly defined in 4E. "Sneak", for example, combines "Move Silently" and "Hide in Shadows" from previous editions. This again makes characters which are less differentiated from each other, but makes a character's skills much easier to read and use. Gone from the skill list are all professional and musical performance skills. So, skills that made a character stand out as unique in some non-combat circumstances are gone. Examples of missing skills include "Perform: String Instruments", "Knowledge: Engineering", and "Profession: Mason". Still present are some information gathering, thieving, and diplomacy skills, so there is still some support for non-combat skill use. As with many other rules sub-systems, the distinctions between character Classes is blurred when it comes to skills. One of the 4E Feats gives characters an extra Trained Skill of their choice. The existence of this Feat means that, differences in Attribute Scores and races aside, any character of any Class can instantly be as good as a member of a class that is supposed to be specialized in the use of that skill. I found this pretty dissatisfying, because the whole point of the class system should be to make archetypical characters, and if the archetypes don't really excel at their chosen bailiwick compared to others, it makes me wonder why D&D is using a class-based system at all in 4E. Sometimes I want my character to be skill-based; I want that to be what makes the character shine. The new skill system undermines those specialized characters by allowing pretty much anyone to be as good as them at almost anything.

Powers & Feats Feats are typically minor special abilities or bits of character trimming that help customize a character that last little bit. Many of them can be chosen by any character, but a good number of them can only be chosen by specific races or Classes. They typically are not as powerful as Class-specific powers, nor indeed are most of them as powerful as some of the upper end Feats in 3E. Feats are plentiful - characters get one starting Feat (two for humans) and then get a new Feat at every even Level thereafter. There is also a fairly long list of Feats to choose from, though some are unavailable to characters until they reach higher Levels.

Multi-Classing Multi-Classing restrictions are nominally only a marginal limit on obtaining proficiency in the trappings of a different Class. Armor and weapon proficiencies and skill training are all acquired via Feat expenditure. Classes specializing in weapons and armor merely get those Feats for free as a Class Feature. There are no rules preventing armored bow-wielding wizards who are tracking experts, so if you are willing to spend the requisite Feat slots you can acquire those abilities without actually multi-Classing. Multi-Classing in 4E really lets you gain access not to the external trappings of another Class, but to that other Class' list of powers, most of which are combat-oriented with a minority of utility powers.

Tiers When a character reaches 21st level he picks an Epic Destiny, which may edge his character toward becoming a historically famous archmage, toward demi-godhood, or perhaps toward immortality. This really gives high level characters a goal both in terms of role-play and in terms of actual powers to provide structures to very high level campaigns.

Races, Classes, and Roles Races grant a variety of specialized powers and bonuses to some Attribute scores. Gone are the race-based Attribute score penalties from earlier versions of D&D. So a character's lowest Attribute in 4E is often higher than his lowest Attribute would have been in 3E. There is very little "fluff" in the PHB - it's almost all rules text (or "crunch"). What little fluff there is in the section on races hints at higher powers and other planes of existence from which some monster and character races originated. Some of the Classes in the game will be familiar to players of 3E, some are brand new, and some of the previous Classes didn't make the cut. Classes are divided into a variety of game-based roles. Defenders (Fighters and Paladins) practically demand that you fight them or you take a beating if you challenge their nearby allies. Fighters are a little more about straight up nose-to-nose fighting, while Paladins represent holy warriors with healing powers and a penchant for martyrdom. Strikers (Rogues, Rangers, and Warlocks) want to avoid damage, and are more lightly armored than Defenders, but they can deal extreme damage to people who get in their sights. While there are some Rogue powers that focus on thieving, Rogues, like all Classes in 4E, are strongly focused on combat. Rogues are reasonable combatants, but do painful things to people that they manage to achieve some kind of combat advantage over. Rangers are not the Grizzly Adams, animal befriending, or spell-casting woodsmen of previous editions - they are all about movement and damage. Contrary to the description of Rangers as being formidable woodsmen, with a single Feat expenditure a Rogue is every bit as good a tracker and woodsman as a Ranger. Rangers have powers named after natural creatures, but few, if any of their powers are particularly tuned toward nature. If you think of the two-blade wielding bowman Aragorn in the Lord of the Rings movies, 4E Rangers capture his combat abilities, but perhaps little else. Warlocks are effectively users of arcane magic who have made a pact with creatures beyond the stars, with infernal powers, or with creatures of the deep wood. Their primary powers involve curses. The Warlock's Pact, chosen at character creation, can influence his selection of powers for the rest of his career, as some Warlock powers work a little better for Warlocks who have a specific kind of pact. Leaders (Clerics and Warlords) specialize in boosting others. They have reasonable combat abilities themselves, but are really there to make their allies perform better. Clerics are priests who enhance their teammates by healing them. While clerics of different deities have some distinguishing characteristics, in general they heal and attack. Gone are Clerical spell domains from earlier editions - 4E Clerics are actually more limited in the diversity of their talents than even 1E Clerics. They are, however, fantastically more able to heal on the fly than any priest Class before, often healing and attacking simultaneously, without taking the time out to play medic. Warlords attack, but either through intelligent tactics or through the power of personality, they direct, support, and choreograph the actions of their allies. The only Class in the Controller role is the Wizard. Wizards are unlike those in previous versions of D&D - their powers are substantially less diverse. 4E Wizards are closer to evocation-specialists, that primarily distinguish themselves through the different flavors and means by which they sling damage. Most spells that involve illusion, the undead, enchantment, powerful divinations, and powerful transport are either very high level, substantially limited, or gone from the wizard's list of potential abilities altogether. For example, to create the illusion of a deer grazing now requires 10 minutes of casting time, 500 gold pieces of components, and a 12th level caster. Scrying abilities that were available to 5th level mages are now the province of mages from 16th to 28th level. For GM's wanting to run epic quests, this is a major plus. Now a mid-level wizard can't scry on the mountain, take the ring of doom, teleport it half way across the continent, protect himself from the volcano at his destination, and fly off into the heavens all before lunch. The downside is that wizards seem remarkably flavorless. Wizard players primarily get to make tactical decisions about who they blast and with what type of energy. Sorcerers, Monks, Bards, Druids, Barbarians, and all other sub-Classes of specialist wizards are now gone from the PHB.

Magic and Spells

Both Clerics and Wizards start the game with access to Ritual magic. Wizards automatically gain free access to new Rituals as they gain levels. Clerics have to spend money to get someone to teach them new Rituals (or alternately crib notes off the party Wizard). Unlike Class-based spell powers, Ritual magic, though time consuming, can be repeated ad nauseum provided that you have a well-equipped stockpile of resources and cash. Rituals are a form of magic that takes a lot of expensive components and a long time to cast. Many spells that casters used to cast in previous versions of D&D with a flick of the wrist can now only be cast completely outside of combat. Sometimes this can produce undesirable results. The ability to comprehend an unknown language now requires 10 minutes to cast, so the flavor text noting that "the guttural language of the creatures before you clarifies into something you understand" is laughably implausible. If you've got a foreign-language-speaking stranger in front of you he's unlikely to stand there for 10 minutes while you ignore him and chant incomprehensibly. Given that the spell lasts 24 hours, one might presume that you would simply cast it whenever you are traveling. Unfortunately you must have heard the language to speak it and must have seen the language to read it within 24 hours prior to casting the spell, making the ritual useless for impromptu encounters with strangers. I'm not intending to harp on a single Ritual, but merely attempting to exemplify a trend among some Rituals. Some seem to be to involved for their resulting general utility. Then again, perhaps it is because of their limited utility that they were made Rituals, as there is no limit, other than available cash, to the number of Rituals that an individual Caster may know. Since both Clerics and Wizards have access to Rituals, some of the Class-specific roles from previous editions of D&D are now gone. Wizards can, for example, raise allies from the dead if they know the ritual to do so. While characters can only multi-Class with one other Class, any character can spend a single Feat to become a Ritual Caster. I found this fairly dissatisfying, as Wizards and Clerics had lost almost all their mystique and had already limited their roles to slinging and healing damage. Now, with a mere Feat expenditure, almost any other character in the party can match them in some of the only really esoteric, mystical-feeling abilities left in the PHB. Most powerful divinatory and teleportation-related magics are rituals, and most require higher level casters. Low- and mid-level characters will no longer know everything and teleport around at the drop of a hat. A friend and I both noted that much of the teleportation left in the game is only available at higher levels and is primarily transportation to and from fixed points, reminding us of the science fiction television show Stargate SG-1. There's even the equivalent of "gate addresses" for permanent teleportation circles.

Magic Items Because of a variety of rules changes, lower level characters tend to get access to less powerful items and tend to be less able to access the full powers of their items as often as a higher level party.

Combat Attacks are handled largely as you'd expect from 3E D&D. The attacker rolls a d20, adds his modifiers, and compares the result to the targets defense. In this edition, as noted earlier, there are now 4 different defense scores, and so different types of tactics and special powers can bring down an opponent who has a high defense in one category, but a lower defense in another. The best example of this is the new grappling rules which don't use a character's Armor Class as his defensive score - these rules now use a Strength-base attack vs. a Reflex defense instead (as a quick aside, for those interested, grappling is much simpler in 4E). One interesting new source of beneficial attack modifier is weapon proficiency. Each weapon has a bonus "to hit" that only applies when someone is proficient with the weapon. In previous versions, non-proficiency was a penalty, but people who were proficient were merely the baseline. Now, non-proficient people are the baseline and proficient people are better than the baseline. Different weapons grant different bonuses to hit and do different levels of damage, so since Fighters have proficiency with all simple and martial weapons, they can carry around a small arsenal to pick the right tool for the current occasion.

Classes who had high numbers of Attacks per Round in previous versions of D&D now only have access to multiple attacks when facing multiple opponents. Powers which attack single targets tend to do more damage when they hit, effectively making up for the inability to make multiple hit rolls per Round against a single target. These changes will result in, for example, a one-on-one combat between a higher level monster and a Fighter taking relatively fewer dice rolls and modifier computations than a similar fight in 3E. Wizards, by comparison, don't inflict the ridiculous amount of damage at higher levels that they did in 3E. Instead, they are more likely to have improved range, area, and special effects attached to their powers. Overall, combats have become a real drag for me in 4E. Each player's turn thankfully takes less time to complete due to the reduction in the number of multiple attack sequences per character. That's the good part. The bad part is that for our group, every encounter lasts 45 minutes to two hours. For a major battle, such as the culmination of a quest, I don't mind spending two hours or longer on the combat. For combats with little or no real importance to the plot (like four wandering goblins plus some rats), I really don't want to spend 1/3 of a gaming session resolving them. Most monsters have more hit points than the PCs, and are a chore to cut down. If a combat is going to largely leave the adventuring party largely uninjured and at full strength after its completion, why make it such a time drain to get through? This perception will change from encounter to encounter and from party to party, so GMs running their own custom-built encounters can run them fairly quickly, but GMs running published adventures may face inordinately long combat sessions.

Death, or the lack thereof In addition, a character's combination of Class and Constitution gives him a certain number of Healing Surges per day. Spending a Healing Surge heals a character by 1/4 of his maximum Hit Points, rounded down. A character can skip one attack per encounter to get his "Second Wind", allowing him to spend a Healing Surge. In previous versions of D&D magical healing restored a given amount of health regardless of the maximum Hit Point total of the character receiving the healing. Further, in previous versions of D&D a given character could receive an unlimited amount of magical healing per day. In 4E, most of the magical healing in the game works off of the Healing Surge system, requiring one of the characters involved (often the recipient) to spend a Healing Surge. This limits the total healing that a character can receive during the day, and also calibrates the absolute amount of each healing effect relative to the specific character being healed. Even without magical healing characters can spend any number of their remaining Healing Surges between encounters. Consider that a level 1 Fighter with a 13 Constitution has 28 Hit Points and 10 Healing Surges, effectively totaling up to 98 total Hit Points of damage he can sustain over a prolonged day of adventuring. Additionally, like adventurers in some computer role-playing games, every time a character gets a full night's rest, he heals from all wounds. Characters which are at negative Hit Points and unconscious can't typically spend their healing surges of their own accord. However, the party healers can intervene to make sure those Healing Surges come into play. Magical healing actually works much better on a character with negative Hit Points than on a character with positive Hit Points. Consider a character with 28 Hit Points at maximum and a Healing Surge Value of 7. If the character is at 1 Hit Point and spends a Healing Surge he goes to 8. If he is at -13 (one point away from death, based on his maximum) then any healing resets his Hit Points to 0 and goes up from there (to 7 in this example). So, this example character heals only 7 points if conscious but can heal up to 20 points if on the very edge of death. This produces a bizarre yo-yo effect where a character is in danger of dying and suddenly stands up and is fighting a second later. Even characters untrained in the Healing skill can make a fairly easy skill check to allow another character to spend a Healing Surge.

Monsters tend to do much more damage and hit much more frequently than you might expect as a player of earlier editions of D&D, again in order to artificially create tension during combat. However, if a player character team has at least one character of each one of the major roles (Controller, Defender, Leader, and Striker), then the players will likely be able to sustain more damage than the monsters in the long run. In economic terms, combat has been affected by severe inflation of most of the variables. The one exception to this is perhaps Wizards, who are able to use their effects frequently but do substantially less damage than you might expect of a Wizard calibrated up to fourth or fifth level. The Wizard primarily exists to use area of effect powers to deal with Minions (a new class of monsters with just 1 Hit Point). For parties with all the character roles properly represented, who are facing challenges at or below their level, the new damage and healing mechanics put them in relatively little danger particularly, if they choose to face only one encounter per day. Death does not automatically occur at 0 Hit Points or -10 Hit Points as it did in earlier versions of D&D. Instead, your character dies when he reaches negative X Hit Points, where X is half of his maximum Hit Points. While he is at any number of negative hit points, he has to make a roll to avoid getting worse on each of his turns, and three failed rolls can make your character die regardless of his negative Hit Point total. As a final "get out of jail free card", Raise Dead is now just an 8th level Ritual, castable by Wizards, Clerics, and anyone with the "Ritual Casting" Feat who knows that Ritual. Raise Dead's negative side effects are very temporary and minor compared to the prices characters paid in previous versions of the game to bring a favorite character back from beyond the pale. These changes do not necessarily mean that a party who faces multiple encounters per day is in no danger at all. After the expenditure of many healing surges and most of the group's daily powers, the group will become less able to defend itself. Moreover, this version of D&D is very much a team exercise - if one or more of the major roles are not represented (particularly the Leaders who have the best "buffing" and healing powers), then a group can quickly be in danger against any encounter at or above their level. A party without a Leader can face the chance of a total party kill against encounters which would normally be a cake walk for parties with all roles represented. This version of D&D can require the Dungeon Master to tinker much more with published adventures if his players have fewer than five total characters representing the four basic roles, as that is now the system's expected norm.

The End to the 5 Minute Adventuring Day I still think that some groups will still have "5 minute adventuring days" to be extra cautious and all but preclude death from multiple combats. However, unlike previous versions of D&D, in 4E that will be one possible choice of how to handle adventuring, not merely the only way to survive.

Organization and Editing The book is not well-organized for players learning the system. Many terms and shorthand symbols are used early in the book without first explaining what they are. The actual core rules come very late in the rulebook. The rules are, however, well-organized for character building, which means that the book's organization may be a thorn in your side while you are first learning the game, but the PHB's organizational structure will likely grow on you as you get more used to the game's rules and are using the game for pure reference. The organizational paradigm for powers is inconsistent in the PHB. All non-Rituals are organized by Class, then by level, and then in alphabetical order. Rituals, however, are not listed in the order of their level, but are instead listed entirely in alphabetical order with a spell list at the beginning of the section that is keyed to level order. This caused a bit of cognitive dissonance for me when trying to choose Rituals as compared to other powers. However, since there are relatively fewer Rituals, this may not be of great concern to most people. The game is also not perfectly edited. Several powers gave rise to unanswered rules questions, sometimes key rules are buried in fluff, and I found a few pretty gratuitous editing gaffs (such as what looks like the omission of around 6-8 consecutive words in the description of Death and Dying). Given the scope of the work, though, the copy editing is reasonably good, but the rules are occasionally poorly organized or vague, giving rise to unnecessary questions. While undesirable, this is hardly surprising given that this version of the PHB has a character creation system that is much more intricate than previous versions of the game.

Bridges from the Past If Unearthed Arcana is not enough to push your 3.5 game towards 4E, but you are still hesitant to entirely give up the familiar for the new, Monte Cook's Book of Experimental Might (BoEM) available at RPGNOW.COM, E23, and other PDF vendors might give you some of the same vibe as 4E from a different author. Cook designed the supplement so that when it is added to a D&D 3.5 rules set it will generate his equivalent of D&D 3.75. If you are hell-bent on not giving up your 3.5 campaign, then between BoEM and Unearthed Arcana you can add a lot of the vibe of 4E to your D&D campaign while keeping a more familiar 3.5 structure. 4E does not allow for any kind of reasonable conversion of existing 3E characters, even in broad strokes, so these alternatives may be more appealing for play groups with ongoing 3.5 campaigns that still have some life in them.

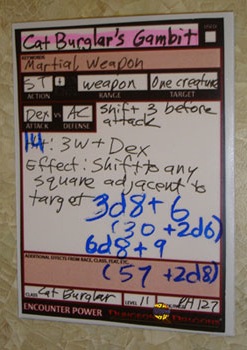

Need for Support Products The range of character powers is appreciated, but in practice, I really needed special cards to write down all the minutiae of my powers. Second edition D&D had such cards for both Priests and Wizards, but I often worked straight out of the Player's Handbook as a player. Previous spells and effects in earlier versions of D&D were often daily powers with simple all-or-nothing effects. In 4E the effects are often usable at-will or rechargeable at the end of an encounter, and they can frequently have a variety of effects which are not simply "hit or miss", all or nothing sorts of effects. Also, many powers in 4E, rather than producing novel effects, are really variations on a theme with miniscule differences which made the powers hard for me to mentally distinguish while playing. These factors, combined with the relative newness of the game, and the fact that even powers that have similar names to earlier editions work in completely unfamiliar ways, really begged for reference material. Some players, especially those with higher level characters, may have their character area littered with photocopies of the rulebook pages. These photos - from Wizards of the Coast, no less - shows that I am not alone in my use of special reference cards.

Wizards of the Coast intends to market blank power cards, but given the detailed nature of some powers, the equivalent of a high end index card for my hand scrawled notations won't really suffice. WotC's new restricted Gaming System License has disallowed companies like Green Ronin from producing some of the support products for 4E that they had planned. So, WotC has left fans to their own devices at the time of launch. Fans online at ENWorld have already started designing many of these cards themselves. When your role-playing space has so many power cards that it looks like a CCG tournament is going on, it's not hard to imagine that some players may come to the conclusion that this game is Dungeons & Dragons in name alone. I didn't feel that way myself, but I can definitely empathize with players who do.

Conclusions While this is a review of the PHB, it is noteworthy that the Dungeon Master's Guide does contain a section on Skill Challenges and non-combat encounters. While this is a refreshing idea given the massive combat bent of the PHB, even the Skill Challenge system tends to treat skill use as a tactical puzzle as much as or more than a role-playing challenge. Unfortunately, the PHB doesn't convey a feel for these mechanics to its reader, giving the reader the impression that combat is really the primary focus of the game. Further, as I will discuss in greater detail in my review of the Dungeon Master's Guide, the Skill Challenge system has some statistical flaws which mean that, in practice, it is not going to function as well as it seems to on paper. While I don't own WotC's first 4E module, Keep on the Shadowfell, according to my Dungeon Master who is running us through the module, it has special rules that encouraged him to undermine my attempts to use skills and role-playing to bypass encounters. The module instead encouraged him to railroad us through one combat encounter after another. If this is WotC's idea of adventure design in 4E, some role-players may feel left out in the cold. Overall, I felt that many aspects of the 4E PHB really screamed "Massively Multiplayer Online Roleplaying Game" and not "Tabletop Fantasy Roleplaying Game". There is a strong focus in the PHB on the use of both miniatures (particularly D&D Miniatures) and a grid map. Many powers and effects in the game (particularly Wizard powers) are entirely tied to a character's position on the table relative to all of his allies and his enemies. This is much more true than it was for any previous version of D&D. Expect players to be constantly jockeying for a specific spot on your battlemat to best use their abilities. Also, more than any tactical miniatures game I have ever played, even for a first level party our battlemat was occasionally littered with status and effect counters (I counted around 10 such counters at one point). This will be a major downside for GMs who hoped for faster and looser styles of GMing that weren't tied to miniatures and maps. The focus on damaging combat powers, as well as the proliferation of status effects, really makes this edition of D&D feel like a tactical miniatures game inspired by the MMORPG scene. Perhaps given the popularity of World of Warcraft, Wizards of the Coast wanted to cash in on that style of game. Perhaps designers at WotC decided that since other games could do narrativist gaming really well, D&D ought to really do a great job of running dungeon crawls. In my playgroup of five players plus a Dungeon Master, three of us said the game ran like a good boardgame or tactical miniatures game. One player hated it altogether. Two seemed to really like it, perceiving it as superior to D&D 3.5. I think this wide range of opinions reflects the fact that the game's systems are not quite as adaptable to a variety of different play expectations and play styles as earlier versions of D&D. Most of this does not have to do with the core chassis of the game. The core combat mechanics are about the cleanest of any version of D&D. However, the options available, both in terms of character creation and in-game play, will leave some types of players to feel like they are playing a completely foreign game that was never intended to include them. I felt that my options as a Wizard were incredibly vanilla and boring. I also thought it was laughable that my character, who was completely untrained in the Healing skill, could, by leveraging the new Healing skill rules, become the third best healer in the party. It was difficult for me to suspend my disbelief. By the end of our last session I eventually gave up all pretenses of role-playing and just started rolling dice and sliding my character miniature around on the battlemat, taking the same actions over and over again on each of my turns. If your D&D games never had much to do with strumming lutes, befriending animals, and playing politics, and always had more to do with slaying dragons and quests for treasure, then you'll likely find this a fantastic version of the Dungeons & Dragons game. If you preferred playing enchantment-casting demagogues, flute playing minstrels, mysterious illusionists, and beast masters - creating a more varied experience overall - then this edition of the PHB will have very little to offer you in the short run. There is some future hope for the latter category of gamers. The cover of the PHB says, "Player's Handbook - Arcane, Divine, and Martial Heroes". This suggests that future expansions might cover the "lost" character Classes, to bring back more character archetypes into the game, and perhaps to expand the powers and skills list. As I said, the chassis of the game could be easily expanded upon with powers, Feats, and skills more appropriate for story-oriented gamers. For now, however, the focus is definitely on hack and slash adventuring, and the PHB seems to support that mode of play in way that's more streamlined and more targeted at "dungeon crawl" enthusiasts than previous versions of Dungeons & Dragons or most other RPG systems currently on the market.

Lee's Ratings

Links:

|

||||

Dungeons & Dragons 4th Edition Player's Handbook

Dungeons & Dragons 4th Edition Player's Handbook As noted earlier, a character gains a flat bonus to all skills (both

Trained and Untrained) equal to half his level, rounded down. This

means that Attributes being equal, a 12th level character is always

flatly better at every untrained skill than a similar 1st level

character who is trained in the skill. This system is fantastically

simpler than 3E skills, and speeds character creation, particularly when

creating a character starting out at more then 1st level. It

distinguishes character Classes at 1st level (where the +5 bonus is

substantial), but it tends to de-emphasize the differences between

Classes at higher levels (where the +5 Trained bonus makes up a

progressively lower percentage of the total bonus). The +5 Trained

bonus makes beginning 1st level characters more competent in their

specialties than their 3E counterparts.

As noted earlier, a character gains a flat bonus to all skills (both

Trained and Untrained) equal to half his level, rounded down. This

means that Attributes being equal, a 12th level character is always

flatly better at every untrained skill than a similar 1st level

character who is trained in the skill. This system is fantastically

simpler than 3E skills, and speeds character creation, particularly when

creating a character starting out at more then 1st level. It

distinguishes character Classes at 1st level (where the +5 bonus is

substantial), but it tends to de-emphasize the differences between

Classes at higher levels (where the +5 Trained bonus makes up a

progressively lower percentage of the total bonus). The +5 Trained

bonus makes beginning 1st level characters more competent in their

specialties than their 3E counterparts.

While Wizards don't, by default, start the game knowing how to wear

heavier armors, spending Feat slots will give access to this ability.

This is important because there are no longer spell failure prohibitions

about Wizards casting spells while wearing armor.

While Wizards don't, by default, start the game knowing how to wear

heavier armors, spending Feat slots will give access to this ability.

This is important because there are no longer spell failure prohibitions

about Wizards casting spells while wearing armor.

In any typical type of attack in D&D, when you hit you do damage, but as

I noted earlier, all character Classes, and particularly characters that

have at least a few levels under their belt, throw around a lot of

status effects. This can make for a lot of counters, markers, and

durations to keep track of during a combat.

In any typical type of attack in D&D, when you hit you do damage, but as

I noted earlier, all character Classes, and particularly characters that

have at least a few levels under their belt, throw around a lot of

status effects. This can make for a lot of counters, markers, and

durations to keep track of during a combat.

This healing mechanism is integral to 4E due to the increased combat

severity of the new system. In previous versions of D&D, first level

characters and their opponents frequently had problems hitting each

other. A "swing and a miss" was a common element of earlier editions of

D&D. This edition has been recalibrated so that players and monsters

alike hit each other much more frequently. This was presumably a

conscious design choice to create the constant sense that something is

always happening. To offset this, all characters and most monsters tend

to have a much larger pool of Hit Points than you would expect at first

level. For example, the first level wizard that I play started with 22

Hit Points. Many creatures in minor encounters (like kobolds) can have

close to 30 Hit Points (compared to the 2-3 Hit Points you might

expect). In many respects, the first level of 4E is effectively the

fourth or fifth level in a previous edition of D&D, merely renormed and

called "first level".

This healing mechanism is integral to 4E due to the increased combat

severity of the new system. In previous versions of D&D, first level

characters and their opponents frequently had problems hitting each

other. A "swing and a miss" was a common element of earlier editions of

D&D. This edition has been recalibrated so that players and monsters

alike hit each other much more frequently. This was presumably a

conscious design choice to create the constant sense that something is

always happening. To offset this, all characters and most monsters tend

to have a much larger pool of Hit Points than you would expect at first

level. For example, the first level wizard that I play started with 22

Hit Points. Many creatures in minor encounters (like kobolds) can have

close to 30 Hit Points (compared to the 2-3 Hit Points you might

expect). In many respects, the first level of 4E is effectively the

fourth or fifth level in a previous edition of D&D, merely renormed and

called "first level".