|

About OgreCave and its staff

|

|

by Gerald Cameron

The Grinding Gear is a module for older (pre- 3rd, arguably pre-2nd) editions of Dungeons & Dragons and modern "retroclone" games like Labyrinth Lord or Swords & Wizardry. It is set in and around an abandoned tavern that was a waypoint for adventuring groups on their way to the untamed frontier. Once its owner - who had no heir - passed away it was abandoned, and now it is, in an ironic twist, a part of the frontier and an adventuring site itself.

Little Tomb of Horrors If anyone was going to publish this kind of dungeon, it was bound to be Raggi. He is the editor and publisher of Green Devil Face, a zine devoted entirely to old school traps and tricks, and a vocal advocate (on his blog and various old school forums) of Dungeons & Dragons as a test of player skill. As you might expect from this, The Grinding Gear does not feature a lot of covered 10-foot pits. Grinding Gear is not a funhouse of poser after poser, as so many deathtrap dungeons are, either. It has a real, if bizarre, premise, and it appears that Raggi did his best to work with that premise. There is even a collection of notes explaining the logic and/or backstory of certain elements of the adventure. In fact, I would suggest that DMs read the module once for basic familiarity, then read the notes, and then reread the module before running it, since you will view certain things differently the second time around. This premise also makes The Grinding Gear as - perhaps even more - suitable a site in a sandbox setting as it is a set piece adventure.

Skill Vs. Fairness Nevertheless, I think there is something to the notion that a good deathtrap, played correctly, with fair warning that such a thing is likely to appear, can be an entertaining exercise for DM and player alike. Unfortunately, each group's idea of fair is going to vary, so the reader needs to know what I think is fair so they can adjust my opinion of The Grinding Gear appropriately. True deathtraps, including save-or-die traps, should be properly foreshadowed or otherwise indicated. Just placing them in an out of the way spot is a random (and harsh) punishment for wandering around. Damaging traps can be more random, but giving players a chance to "solve" them is more interesting. Also, beware of deathtraps that hide behind a die roll (10d100 damage, anyone?) Testing greed and curiosity is fair game, but traps that run directly counter to each other (one trap that nails the greedy followed by a trap that hits those that resist taking a treasure, for example) within the same dungeon is foul play. In particular, I like traps that punish overly "game-y" behavior. I haven't played this style of game in decades, so I may have forgotten parts of standard operating procedure in old editions of D&D that make some traps fairer than they appear. The Grinding Gear skirts the edge of fairness. It demands, with limited and indirect hints, careful observation of the early portion of the adventure and failure to be observant of the right details will probably lead to the PCs death. Also, one misdirection players are likely to fall leads PCs into a 1 in 6 chance of death. There is one key that is hidden in such a way that only those used to this style of play are likely to find it and keep it, too. It will take a bit of luck to get away alive with the treasure, but most groups will only die because of irrational stubbornness or gross stupidity.

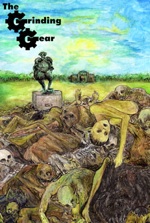

Presentation There are three heavy, glossy cardstock covers that are not bound to the main booklet, reminiscent of the covers of early edition D&D modules. These covers feature maps, a player handout, and the aforementioned designer's notes about certain areas of the dungeon. The player handout also has a decorative piece of black & white art by Laura Jalo on its reverse side. The full-color cover piece is also by Jalo. There are only two pieces of interior art, one full-page and one a small filler piece at the very end of the book. Like the cover pieces, they are by Laura Jalo, whose work I have admired in all of LotFP's books. I think her style may work better in black & white than it does on the full-color cover, but one color piece is hardly a fair test. Raggi writes with a distinctive voice that is pleasant, other than an occasional defensive note when he expects readers to bridle at his "old school" style. I have read enough of Raggi's work that I now notice some recurring stylistic touches, which is rather rewarding. He is free to inject some real flavor into his work, although The Grinding Gear does not have the same moody creepiness as Death, Frost, Doom or No Dignity in Death: the Three Brides. It is still distinctly Raggi's handiwork, though; while he clearly walks the trail blazed during the early years of the hobby, he has a distinct style that I like better than the generic tone of most adventures, classic or modern. There is also little doubt in my mind that the character that built the dungeon is Raggi himself written into the world of The Grinding Gear.

Conclusion

|

||||

The Grinding Gear

The Grinding Gear